Reminiscences of Operating a TID Tug

By W. R. Deeble

'If a bit of personal narrative would add to what you know about the TID's, I operated one from early August to late November of 1944 in the small fishing port of St. Vaast la Hogue. . .'

Internet surfing chanced to bring up your web site, and I was pleasantly

surprised to see the familiar shape I had worked and lived on so long

ago, and which I would have supposed to exist now only in faded photos.

To find that there is a TID not only whole and afloat, but running well

enough to cross the Channel, is somehow very gratifying. Well done, 172

and all her faithful restorers!

Of course

172 is an oil-burner and was built after the war, but she is still part

of the same program as mine, which used coal and was built in 1943; I

would bet that she probably has some of the same quirks of performance

as well. Unfortunately I don't remember the number of mine, but she was

one of a group that was towed across the Channel and handed to the U.S.

Army's 338th Harbor Craft Company after we had landed on Utah Beach from

a transport. Others were distributed to units in Isigny, Carentan, and

similar small ports.

When my seven crewmen and I went aboard for the first time, we were like the buyers of an unknown make of used car, and although we were given a quick briefing on steam, it took a while before we could function effectively. On the bridge it made little difference to me whether the bell signals were answered by diesel, steam, or galley slaves, but the engineer had been trained on diesels, and steam was a new and very different ball game for him. All he or most of us knew was that it hissed a lot, raised hell if the wrong handle were turned, and had enormous explosive potential.

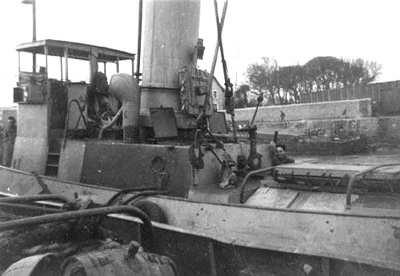

Background is St. Vaast sea-wall

This set up our first excitement: A couple of nights after taking possession we were doing practice maneuvers and paused for a moment to let the engineer attempt some adjustments. There was a sudden hissing, thumping, and shaking, and he came shooting up out of the engine-room hatch, paused dramatically at the rail to yell "She's gonna blow!" and jumped overboard. Not pausing to debate the validity of his warning, the rest of us jumped also.

Fortunately the water was warm, so we paddled around at a safe distance, waiting for an explosion that never came. Instead, the noises died out, and we saw our fireman at the rail, inviting us to come back. He knew nothing about engines, but had tended boiler in a big apartment building and had enough experience with steam not to fear it, so he just went around closing valves until things quieted down. The swimmers crawled back on board, feeling as sheepish as you can imagine, and by common consent nothing was ever said about it to the other boats.

Background is part of village; low-tide state is obvious

Within two weeks that engineer was taking the machinery apart, grinding valves and joints for a better fit, and efficiently lubricating everything that moved. For the rest of the four months the engine ran as smoothly and quietly as a good watch. The fireman managed to keep good boiler pressure with some of the most impure soft coal ever mined, although he once called me below to inspect a collection of giant clinkers he had artistically arranged to cover the entire stokehold floor.

Part of our trouble was being outranked at the coal barge by the orderlies from shoreside offices and officers' quarters who appropriated all the best lumps for their exalted patrons. Even at best, refilling the bunkers was a filthy job, leaving a coating of black dust all over the tug and the crew. (Let's have no more complaints from fortunate effetes who enjoy the convenience and comparative cleanliness of oil!) Unlike other TID's, we had the luxury of a hot shower, improvised by our ingenious engineer's running a steam line into the water tank atop the forward deckhouse.

Taking a break at low tide. Note extra steam line to water tank -- hot showers!

We worked two tides a day during daylight hours, starting as soon as we floated and stopping just in time to tie up to something before the harbor went dry; mostly lightering barge-loads of all sorts of materiel from deep-draft cargo vessels out in the roads to the quays of the port, helping small coasters to berths inside, or maneuvering floating cranes to handle heavy loads. There was always some useful task for us as long as we had enough water to float; if nothing else, we could top off the bunkers.

After dark, or when the harbor was dry we were at liberty to sleep or explore the village and the nearby shore, being cautious around the remains of the German defense system. It was a remarkably free existence for an army unit, being left so much to our own devices.

Background

is fighter wing-tanks, typical barge-load for us to haul in from anchored

freighters.

After accommodation was shared by four of us; no "officers' country"

in so small a vessel.

Periodically we would be annoyed by the kind of colonel who infests the rear areas of all armies, and who seemed particularly offended that our deckhands wore sailor hats, blue denim shirts, and dungarees, instead of the standard GI fatigues. However, some smart planner had decided that nautical attire was better for nautical duties, so that was what we had been issued. The colonel could only mutter sullenly about the gross dereliction from soldierly appearance.

Back:

Horn (Seaman), Shertzer (Fireman), Helm (Cook), Costello (Seaman)

Front: Hebert (Seaman), Schessler (Engineer), Martz (Fireman)

Primary duties indicated, but everyone did a bit of everything as needed;

small craft can't afford specialists!

The capture of Antwerp made the beaches and their attendant small ports redundant, so we closed out St. Vaast and moved our tugs and barges to Rouen, where we changed back to more familiar diesels and said farewell-with few regrets!--to steam and TID's. It had been a coal-grimed and often laborious experience, but by comparison with the hardships and dangers of the rest of the army, we were very fortunate. In four months we never saw a German plane, and gun-camera films of our planes strafing enemy tugs and barges remind me what a target we could have been. I remain grateful to the Allied fliers who so effectively guarded us from the attentions of the Luftwaffe.

Best wishes to TID 172 and her maintainers-long may she steam!

W. R. Deeble (ex-W.O.J.G., A.U.S.)